Professor Brett Kahr is Senior Fellow at the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology in London, Honorary Director of Research and Honorary Fellow at the Freud Museum London, and Visiting Professor of Psychoanalysis and Mental Health at Regent’s University London. Kahr serves as Chair of the Scholars Committee of the British Psychoanalytic Council and as Consultant Psychotherapist at The Balint Consultancy. His many books include the bestselling ‘Sex and the Psyche’ and ‘How to Flourish as a Psychotherapist’.

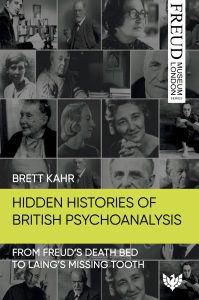

Brett’s latest book ‘Hidden Histories of British Psychoanalysis: From Freud’s Death Bed to Laing’s Missing Tooth’ draws upon extensive unpublished archival sources and four decades of oral history interviews to paint fascinating portraits of many of the icons of mental health.

Four Vibrant Grandparents

I shall never forget that, as a young boy, the vast majority of my contemporaries rarely talked about their grandparents. Most of them had already buried their grandmothers and grandfathers or had spent little time with them owing to the frailty of those ageing relatives. By contrast, I had the good fortune to have grown up in a family which bred early; hence, as a newborn, I had the privilege of enjoying the company of no fewer than four grandparents, all in their forties – a rarity nowadays – hence, I found ‘old’ people very engaging and very interesting indeed.

Indeed, my childhood interviews with my grandparents, in which I quizzed them regularly about their ancestors, no doubt stimulated my interest in the grandparental and great-grandparental figures of the psychoanalytical community.

The Elderly Psychoanalysts

As a young undergraduate psychology student, I became enraptured not only by all of the research in this field (ranging from cognitive psychology and empirical psychology to psychopathology and social psychology) but, also, with the lives of the founders of the profession. And, quite early on, I began to conduct oral history interviews with as many of the elderly members of the psychological community as possible.

I feel very privileged that, at the tender age of twenty-three, I arranged to meet none other than Dr Muriel Gardiner – a brilliant American psychoanalyst who had actually trained in Vienna decades previously and who had even enjoyed the privilege of shaking the hand of Professor Sigmund Freud. I invited Dr Gardiner to speak in Oxford and she delivered a wonderful talk about her time in Austria. Shaking the hand of someone still living who had shaken the hand of Freud exerted a hugely positive impact, I must say!

In due course, I conducted interviews with virtually every single septuagenarian, octogenarian, and nonagenarian whom I could locate, ranging from Dr John Bowlby and Mrs Enid Balint to Mrs Marion Milner and Miss Pearl King, not to mention Dr Hanna Segal, Dr Charles Rycroft, and Dr Ronald Laing, and literally hundreds of other pioneers of British psychoanalysis.

Although I feel very privileged to have studied with some remarkable teachers and clinical supervisors while pursuing my trainings, these ancient icons taught me so much about the art of clinical practice and passed on their wisdom with such generosity that I must confess that I learned more from these leaders than from all of my instructors combined.

Hidden Histories of British Psychoanalysis: From Freud’s Death Bed to Laing’s Missing Tooth

During the coronavirus pandemic, I had little opportunity to socialise; hence, I devoted much more time to writing than ever before, and I derived great pleasure from composing a long-brewing history of many of the leading personalities from the British psychoanalytical movement. I have included none other than Sigmund Freud as a ‘British psychoanalyst’ because, as one knows, he did practice in London between 1938 and 1939, having escaped from Nazi-invaded Austria, and, in the first chapter, I explain how Freud first learned English and had already begun to treat both American and British patients.

derived great pleasure from composing a long-brewing history of many of the leading personalities from the British psychoanalytical movement. I have included none other than Sigmund Freud as a ‘British psychoanalyst’ because, as one knows, he did practice in London between 1938 and 1939, having escaped from Nazi-invaded Austria, and, in the first chapter, I explain how Freud first learned English and had already begun to treat both American and British patients.

Thereafter, I explore Dr Donald Winnicott’s amazing work in the field of child psychoanalysis, having had the privilege of drawing upon the private archives of none other than that of his famous patient, ‘The Piggle’, whom I first interviewed in 1996. I then examine not only the pioneering work of Dr John Bowlby as well as my reminiscences of such an inspiring man, but, also, I share the interviews that I conducted with his super-brilliant wife, Mrs Ursula Bowlby, who championed dynamic psychology in her own manner.

I also investigate the lives of many genius women, including Mrs Enid Balint and Mrs Marion Milner. And I then conclude with very revealing examinations of the ‘shadow’ side of Mr Masud Khan and Dr Ronald Laing – two incredibly brilliant men who, nevertheless, misbehaved from time to time and, sadly, have brought psychoanalysis into great disrepute in the eyes of many.

I hope and trust that younger colleagues will also embrace the history of psychoanalysis, not only as a means of learning from the most experienced clinicians on the planet, but, also, as a way of immersing themselves more fully into the field through personal engagement with inspiring characters.

Professor Brett Kahr

Buy your copy of ‘Hidden Histories of British Psychoanalysis: From Freud’s Death Bed to Laing’s Missing Tooth’ now!