Dr Harvey Schwartz is a training and supervising analyst at the Psychoanalytic Association of New York (PANY) and at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia (PCOP). He currently serves as the chair of the International Psychoanalytical Association in Health committee. He is a contributor to and (co)editor of four books including Psychodynamic Concepts in General Psychiatry and Illness in the Analyst: Implications for the Treatment Relationship. He is the producer of the IPA podcast Psychoanalysis On and Off the Couch and is the founder of the Jewish Thought and Psychoanalysis lecture series and website.

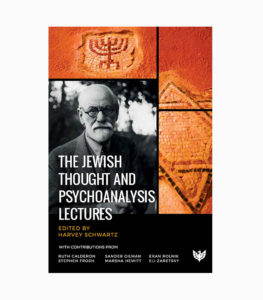

Here are his thoughts on psychoanalysis and religion to accompany the publication of his excellent new edited work The Jewish Thought and Psychoanalysis Lectures containing contributions from Eli Zaretsky, Stephen Frosh, Sander L. Gilman, Marsha Aileen Hewitt, Eran Rolnik, Ruth Calderon, and Harvey himself.

Psychoanalysis and religious belief have a long and fraught relationship. Like siblings they share some common origins yet claim their own uniqueness. They each see themselves as representing deep truths about the human experience yet struggle to acknowledge the wisdom claimed by the other. At the extremes, adherents of one world view see those of the other as misguided if not malevolent.

Both the psychoanalytic and religious worldviews posit that the profundity of life lies in other than that which meets the eye. Psychoanalysis represents this great unseen in their notion of the internal unconscious while those who are religiously inclined attribute it to external divine forces. What is called scientific data as to the existence of these hidden realms is lacking for both schools. Hence, without this limit-setting ability of objective evaluation, each of these theoretical realms proliferate and end up encouraging offshoots based on passionate subjective claims of greater truths. Theological and psychoanalytic splits are common.

which meets the eye. Psychoanalysis represents this great unseen in their notion of the internal unconscious while those who are religiously inclined attribute it to external divine forces. What is called scientific data as to the existence of these hidden realms is lacking for both schools. Hence, without this limit-setting ability of objective evaluation, each of these theoretical realms proliferate and end up encouraging offshoots based on passionate subjective claims of greater truths. Theological and psychoanalytic splits are common.

One quality that both views share is the necessity of consensus – their adherents demand from each other that they accept certain basic understandings of the world that exist outside the realm of verifiable reality. The absence of the objectivity of the various claims is seen as adding even deeper meaning to the subjective truths. Idiosyncratic meanings, when shared by others, unites the adherents in greater solidarity. A shrine that is venerated and considered ‘holy’ by one sect is seen as mere stone by another. Such a difference can become the basis for killing the outsider, now experienced as a threatening heretic.

In psychoanalysis death is not the vehicle of disapproval – rather shunning has been more widely practiced. If one practitioner values early trauma as pathogenic, she may be viewed derisively by someone who privileges the fantasy life of the four-year-old as responsible for adult troubles. Actual objective testing of these hypotheses is sought by neither adherent. Artwork, literature and philosophers would sooner be brought forth as evidence for one or another theory then methods developed to study the clinical impact of interventions derived from one or the other of these perspectives.

It is when such clinical investigations are undertaken that the truths underlying religious and psychoanalytic theories separate from each other. Religious meanings always revert to the particular notions attributed to their deity to declare their unarguable validity. In contrast, clinical psychoanalytic ideas are tested, dismissed, reexamined and refined in the encounter with the analysand. In the clinical crucible, psychoanalysis takes on a vibrancy that allows each encounter to be its own creation. The minds of each of the participants work together to reveal the truths that are the analysands. These truths do come to reveal that which is hidden from view, and the reasons for their hiding as well. That these memories, imaginings, and affects are hidden becomes more then religious dogma – it becomes a discovered truth. A truth that could not have been known nor predicted before the journey began.

The similarities that religious and psychoanalytic conceptualizations share, that hidden meanings are vital in our lives, diverge in the face of the differing methods of discovery of these meanings and the acknowledgement of their individualized origins.

Yet, the tensions between the psychoanalytic and monotheistic worldviews continue to enrich each other. The unseen deity, like the unseen analyst, encourages the elaboration of one’s imagination freed from the encumbrances of literal graven images. Freud’s cultural experience of being the outsider, the alien Jew, deepened his capacity to experience himself simultaneously as participant and observer in the minds of his analysands. His self-described identity as a “fanatical Jew” applied as well to his devotion to his creation of psycho-analysis – more accurately translated as the study of the soul.

Harvey Schwartz