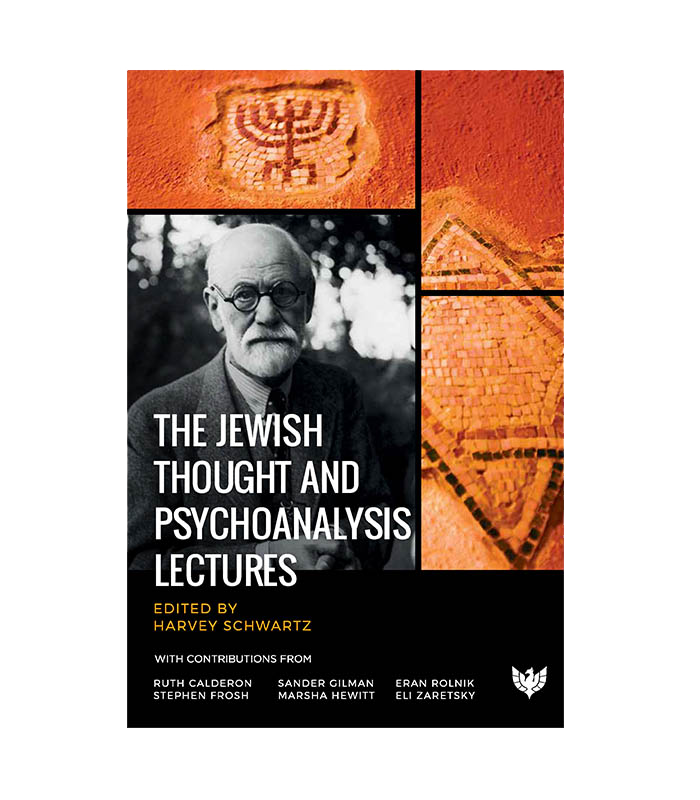

Freud’s relationship with his Judaism – his by virtue of his self- description as a “fanatical Jew” – was framed by two of his convictions. He was centered both by his passionate cultural affiliation and by his atheism. Within these internal guideposts lay a Jewish life layered by tensions, pleasures, and identifications. His creation – psychoanalysis – has labored to honor its Jewish influences. Recent studies of these insights have contributed to the current interest in listening more carefully to the individual meanings of analysands’ religious life.

This lecture series was designed to introduce to the public both the similarities and the differences between the psychoanalytic and the Jewish world views. The contributors are among the thought leaders of our generation who work at the interface of the intrapsychic and religious states of mind. We learn how each has influenced the other and perhaps how each has been enriched by the other.

A tour de force delving into the influence of Freud’s Jewish roots on the development of psychoanalysis.

Dr Harvey Schwartz is a training and supervising analyst at the Psychoanalytic Association of New York (PANY) and at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia (PCOP). He currently serves as the chair of the International Psychoanalytical Association in Health committee. He is a contributor to and (co)editor of four books including Psychodynamic Concepts in General Psychiatry and Illness in the Analyst: Implications for the Treatment Relationship. He is the producer of the IPA podcast Psychoanalysis On and Off the Couch and is the founder of the Jewish Thought and Psychoanalysis lecture series

Dr Harvey Schwartz is a training and supervising analyst at the Psychoanalytic Association of New York (PANY) and at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia (PCOP). He currently serves as the chair of the International Psychoanalytical Association in Health committee. He is a contributor to and (co)editor of four books including Psychodynamic Concepts in General Psychiatry and Illness in the Analyst: Implications for the Treatment Relationship. He is the producer of the IPA podcast Psychoanalysis On and Off the Couch and is the founder of the Jewish Thought and Psychoanalysis lecture series

Susannah Heschel, Eli Black Professor of Jewish Studies, Dartmouth College –

‘This fascinating collection analyzes aspects of Judaism and Jewish history from a perspective that is deeply informed and rich with psychoanalytic theory. The authors offer remarkably original insights about the nature of modern Jewish identity and subjectivity and also about the origins, development, and cultural significance of psychoanalytic treatment.’

Peter Loewenberg, Professor of History and Political Psychology, Emeritus, UCLA; Training & Supervising Analyst and Past Dean, New Center for Psychoanalysis, Los Angeles –

‘This is a rewarding series of lectures with rich and expert exegesis of both Biblical Judaism and psychoanalysis, the Jew as the symbolic feminine, forgiveness, spiritual, mystical, and unconscious communication, Israel, and Judaism. Harvey Schwartz’s introductions to each lecture are personal, intimate, and refreshing. The book poses many stimulating questions for the reader.’

Bennett Simon, MD, Training and Supervising Analyst, Emeritus, Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute; Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Emeritus, Harvard Medical School and the Cambridge Health Alliance –

‘This collection provides a rich resource for expanding and deepening the dialogue between psychoanalysis and Judaism. The range of topics and approaches encourages more imaginative critical thinking about the diversity that is within both Judaism and psychoanalysis. The editor’s introductions and his own collaborative chapter, a dialogue between a psychoanalyst and a teacher of Talmud, make the volume readily accessible to readers more broadly interested in religions and depth psychology.’

Merav Roth, PhD, training psychoanalyst, Israeli Psychoanalytic Society; chair, psychotherapy program, Tel Aviv University; author of A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Reading Literature –

‘The various papers edited in the present book shed light on the interconnectedness between psychoanalysis and Jewish thought, exploring the rooted link between these two fields of wisdom and practice. It touches daringly upon the unconscious levels of Jewish-psychoanalytic theories about the mind, spirit, and body. It offers a mosaic of diverse, original perspectives illuminating this link through biblical, philosophical, psychoanalytic, social, and Talmudic texts. The Jewish influence on psychoanalysis is viewed through a historical perspective (anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, Zionism, and current history), as well as a religious and even a mystical viewpoint. In the book we meet familiar cultural heroes, such as the Biblical characters of Moses and Miriam, paradigmatic texts as The Dybbuk and great thinkers both in the psychoanalytic field and otherwise. In all the collection of papers, a fascinating inter-disciplinary encounter is created, which enriches the reader in an innovative and enlightening manner. As said by the Talmudist Ruth Calderon in the last chapter – “There’s a belief that the text is waiting for you personally and that God hid a little note with your name on it in the text.” I am certain that every reader will find the note waiting for his conscious and unconscious riddles regarding the relation between psychoanalysis and Jewish thought.’

Josh Cohen, Fellow of the British Psychoanalytical Society; Professor of Modern Literary Theory, Goldsmiths University of London –

‘Encompassing contributions from leading thinkers in both fields, addressing topics from Moses to mysticism, trauma to forgiveness, hysteria to sexuality, this fine collection of lectures brings home the vast richness and continued vitality of the dialogue between Judaism and psychoanalysis. The sharpness and originality of the thinking presented here is fully matched by the liveliness and accessibility of the writing.’

Arnold Richards, M.D., psychoanalyst and former editor of The American Psychoanalyst and Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association –

‘Harvey Schwartz, the editor of the volume, writes erudite introductions to each chapter and … deserves our gratitude for organizing this lecture series and publishing the volume. It should be widely read.’

Gordon Alderson, Attachment Vol. 15 No. 1 –

‘”The Jewish Thought and Psychoanalysis Lectures” offers us a strikingly varied menu of thoughts and perspectives which gives rise to the quite unexpected.’

Val Simanowitz, counsellor and supervisory – Therapy Today Sept 2020 –

‘fascinating in pointing out the history of psychoanalysis, its trajectory and its strong links to Freud’s Jewish identity and Jewish thought. Many of these concepts continue to influence therapeutic practice today.’

Shmuel Erlich, The Hebrew University, ‘Becoming Post-Communist: Jews and the New Political Cultures of Russia and Eastern Europe’ –

‘timely and pertinent […] The dialogue between the two protagonists — one, a female talmudic scholar, the other a clinically practicing psychoanalyst — is fascinating. This final discussion also serves to complete the circle of looking at the ways in which Jewish thought and psychoanalysis have influenced and fertilized one another, and how some aspects of this union are viewed through the lens of current social issues.’